Abstract

We conducted a large-scale ablation of 20 system prompts across two Qwen3 models (30B MoE AWQ-4bit on vLLM; 8B q4_K_M on Ollama), two recipe complexities (3-step spaghetti vs. 21-step lasagna), five random seeds, and 30 iterations per chain (total: 500 runs, 15,000 inferences). Cosine similarity to the original was computed via Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B.

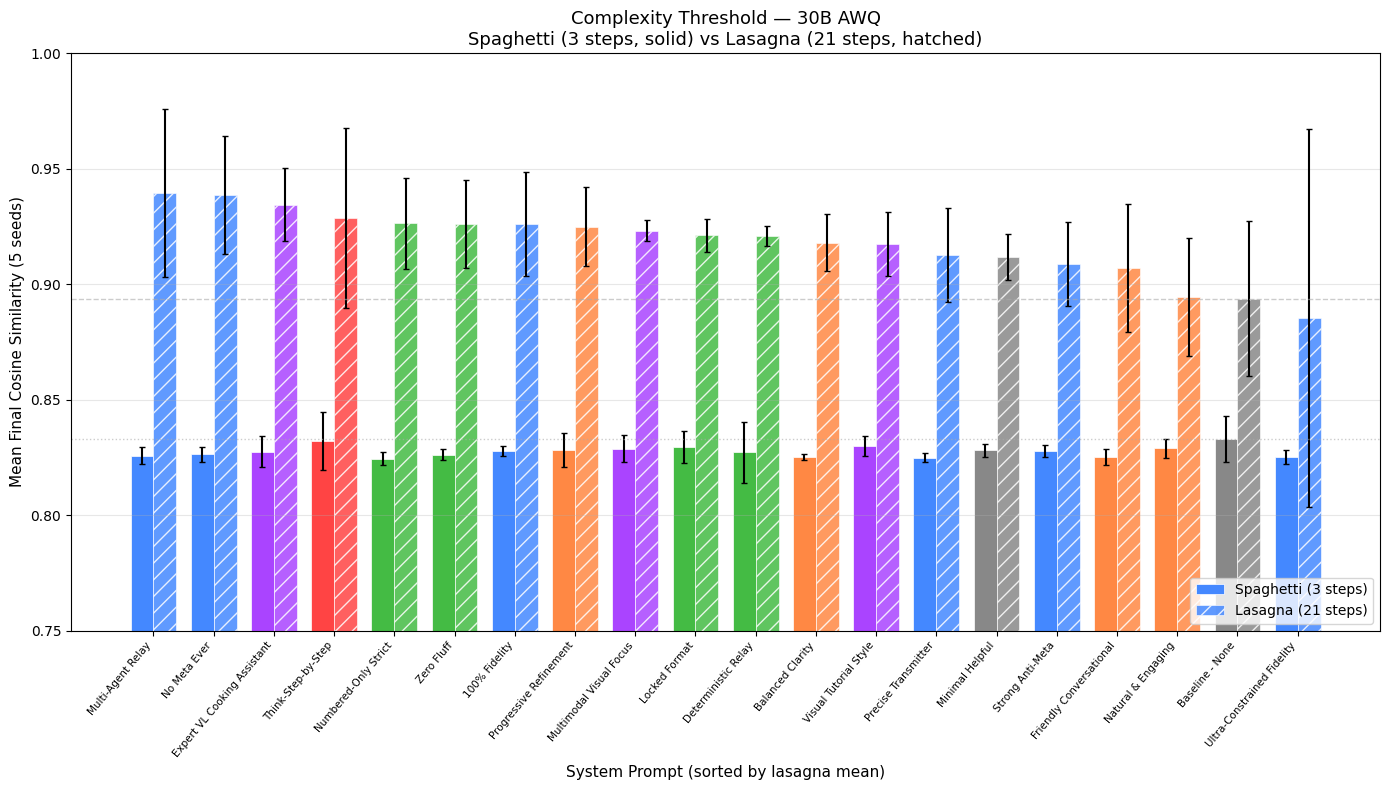

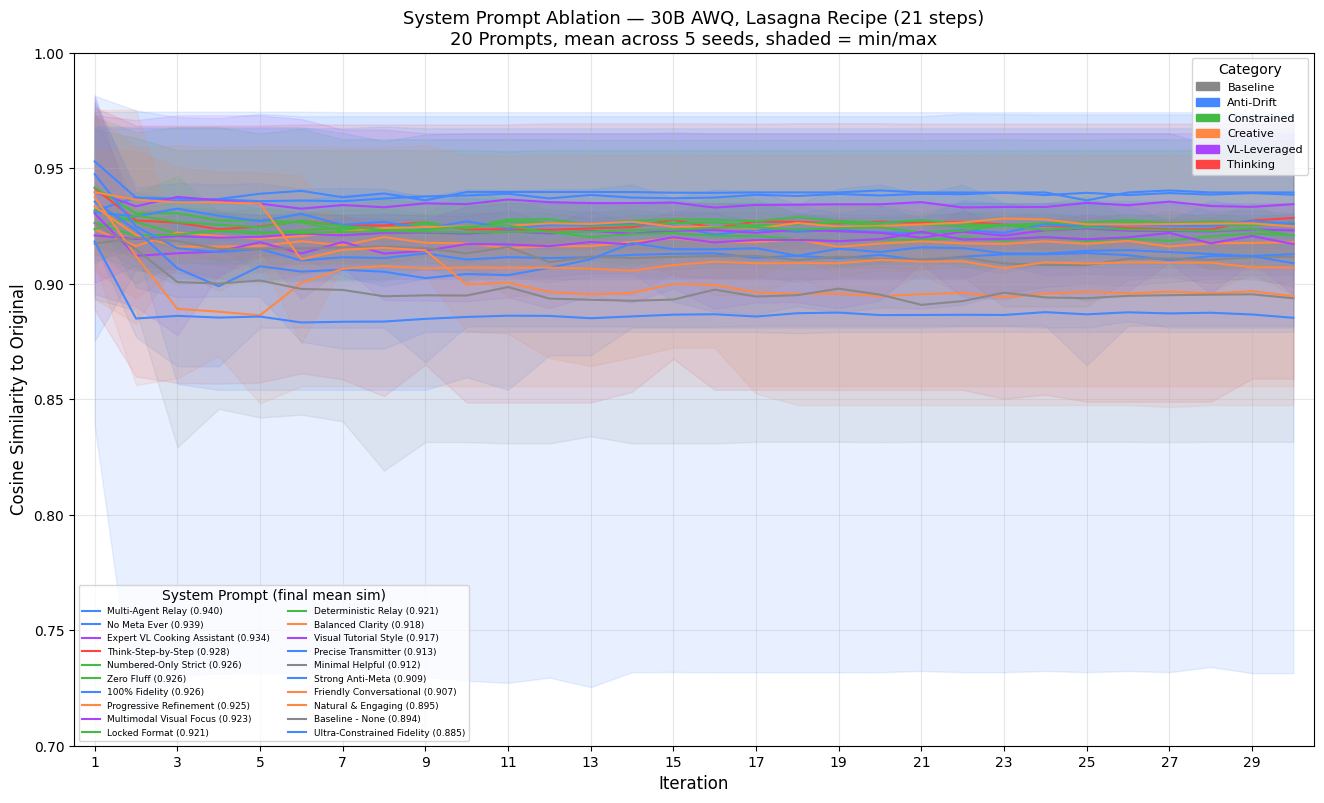

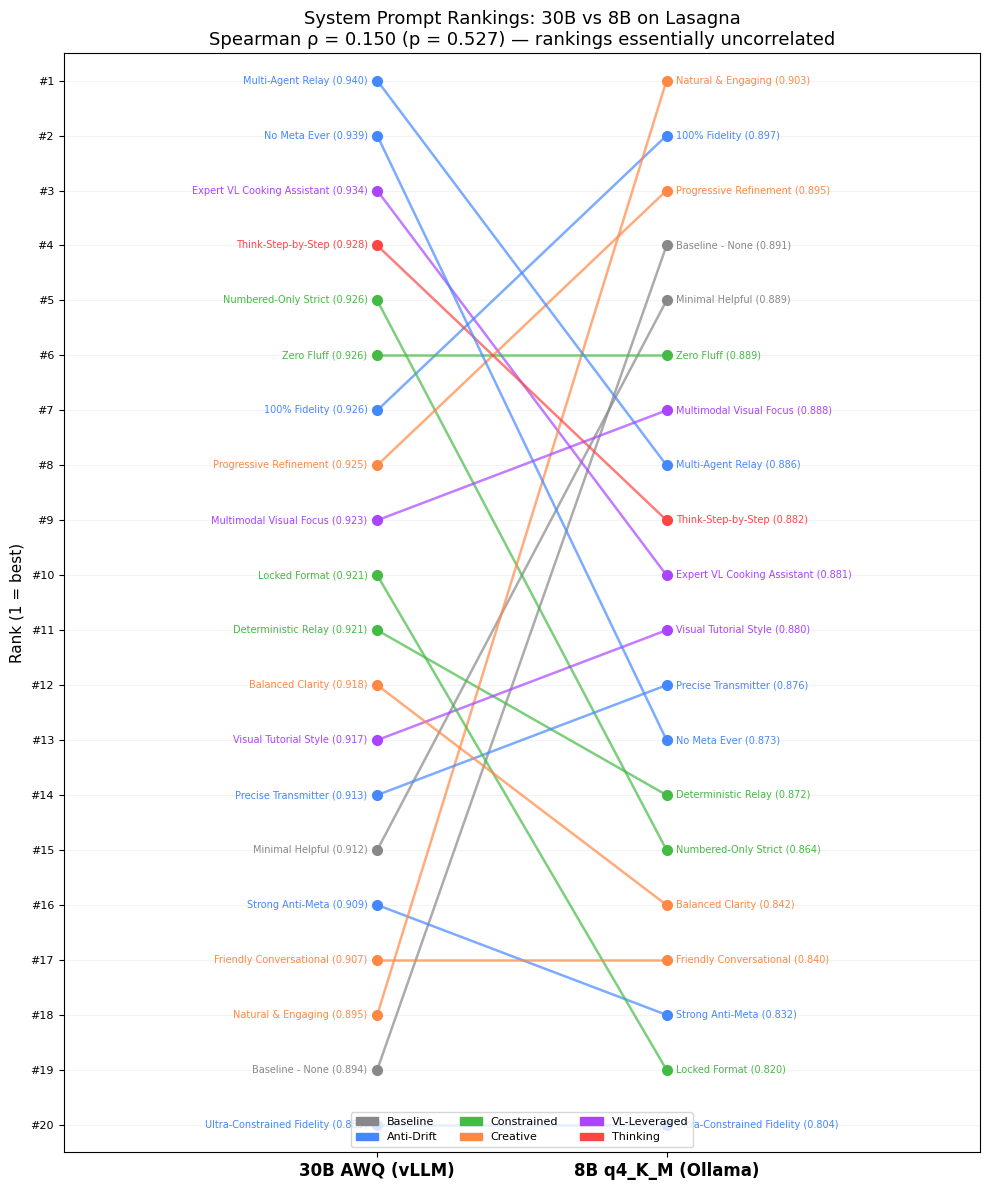

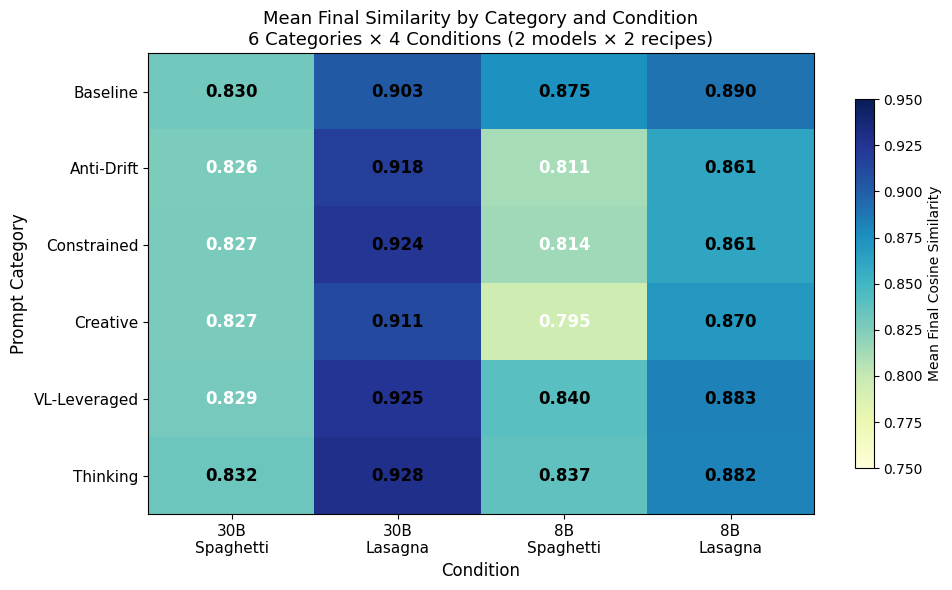

Key findings: (1) System prompts are invisible below a complexity threshold—on the 3-step recipe, all 20 prompts produced identical performance on the 30B model (spread 0.008). On the 21-step recipe, spread widened 7× to 0.054. (2) Prompt effectiveness is model-size dependent: anti-meta prompts targeting explicit meta-commentary achieve 0.940 on 30B but rank mid-pack on 8B; creative/baseline prompts top the 8B ranking (0.903). Spearman rank correlation between models: ρ = 0.15 (p = 0.53). (3) Fixed-point attractors appear in 54% of 30B lasagna runs; system prompts select which basin the chain settles into.

These results extend Perez et al. (2025) on instruction-modulated attractors and Mohamed et al. (2025) on iterative distortion, while revealing a previously undocumented interaction between prompt complexity and model capacity limits (Jaroslawicz et al., 2025). Rankings invert across model scales, confirming that prompt engineering for agent pipelines must be empirically validated per deployment profile.

Introduction

Parts 1 and 2 of this series established two foundational truths about semantic drift in local LLM agent pipelines. Part 1 (17 open-weight models, simple 3-step recipe) showed that model choice dominates: Qwen3-30B-instruct preserved 0.91 similarity after 30 paraphrases, while Llama-3.1-8B collapsed to generic customer-service boilerplate at 0.20. Drift was not random noise but convergence to model-specific cultural attractors—meta-agent framing in “-next” variants, clinical language in MedGemma, structured lists in coder models.

Part 2 isolated infrastructure: toggling Ollama’s KV cache from default fp16 to q8_0 produced swings up to +0.62 (tiny models) and –0.36 (large MoE “next” variants). The serving layer is not neutral; precision choices reshape attractor basins.

Both papers ended with the same open question: can system prompts steer chains toward high-fidelity attractors? We speculated that strong anti-drift instructions would reduce drift, creative prompts might amplify it, and complex recipes would expose larger prompt effects. This third installment tests those hypotheses at scale.

The results are more nuanced—and more sobering—than anticipated. System prompts matter, but only above a clear complexity threshold and only when they target the model’s dominant failure mode. Most importantly, the optimal prompt for a 30B-class model is often mediocre or actively harmful on an 8B-class model. The ranking inversion (Spearman ρ = 0.15) demonstrates that prompt engineering is not portable across scale.

This has immediate consequences for anyone building multi-agent systems, RAG relays, self-refinement loops, or any pipeline that passes procedural instructions between LLM calls. The “best” system prompt is a function of model size, task complexity, and failure-mode profile. Single-turn benchmarks and generic “be faithful” templates are insufficient. Empirical telephone-game testing at pipeline depth is required.

Related Work

The telephone-game paradigm for LLMs was formalized by Perez et al. (2025, arXiv:2407.04503, ICLR 2025). They transmitted human-written stories across chains under three instructions (“rephrase”, “take inspiration”, “continue”) and tracked toxicity, positivity, difficulty, and length. Instruction openness modulated attractor strength: constrained “rephrase” tasks produced weaker attractors than open-ended ones. Our 20 prompts deliberately span that spectrum.

Mohamed et al. (2025, arXiv:2502.20258, ACL 2025) demonstrated iterative distortion in both translation (English–Thai–English) and pure rephrasing chains. Factual details degraded rapidly (a lorry accident became a bus explosion by iteration 50), but low temperature and highly restrictive prompts (“preserve every fact exactly”) provided partial mitigation. Our work extends this to system-level control in agent pipelines and reveals that “restrictive” is not monolithic—ultra-constrained prompts can backfire by creating internal contradictions.

Recent dynamical-systems analyses provide mechanistic grounding. Wang et al. (2025, arXiv:2502.15208) treated successive paraphrasing as an iterated map and discovered stable 2-period attractor cycles in output space, limiting linguistic diversity even under temperature sampling. Chytas & Singh (2025, arXiv:2601.11575) modeled intermediate layers as contractive mappings in an Iterated Function System converging to concept-specific attractors. Our fixed-point observation (54% of 30B lasagna runs lock to period-1 orbits) is the direct empirical counterpart: system prompts select which basin the trajectory enters.

Instruction-following capacity limits explain the model-size inversion. Jaroslawicz et al. (2025, arXiv:2507.11538) introduced IFScale, a benchmark injecting up to 500 simultaneous keyword constraints into a report-writing task. Even frontier models degrade sharply above ~100 instructions; smaller models collapse earlier and exhibit stronger recency bias. Our 21-step lasagna + complex system prompt exceeds the 8B model’s effective capacity budget, while the 30B model treats the system prompt and recipe steps as separate instruction sets it can jointly satisfy.

Broader cultural-evolution framing comes from Brinkmann et al. (2023) “Machine culture” (Nature Human Behaviour) and subsequent LLM-population studies showing spontaneous convention emergence and collective bias amplification. Our single-model chains already exhibit attractor convergence; multi-model pipelines will likely accelerate it.

No prior work has systematically ablated system prompts across model scales and task complexities in a controlled telephone-game setting. This study fills that gap and reveals the non-transferability of prompt strategies across the deployment spectrum.

Methodology

Models

- 30B: Qwen3-VL-30B-A3B (AWQ 4-bit) via vLLM (port 8005) — strong instruction-follower with VL pretraining.

- 8B: Qwen3-8B (q4_K_M weights, q8 KV cache) via Ollama (port 11434) — representative local-deployment tier.

Recipes

Full texts in appendix.

- Spaghetti (3 semantic units): “Step 1: Boil water. Step 2: Add pasta for 8 minutes. Step 3: Drain and serve with sauce.”

- Lasagna (21 steps): detailed beef lasagna with exact measurements (1.25 lb ground beef, 0.75 lb sausage, 375°F, 9×13 pan, layering sequence, rest 15 min).

System Prompts

20 total across 6 categories. Representative examples:

Baseline

- None (empty)

- “You are a helpful assistant.”

Anti-Drift (target meta-commentary or fidelity)

- Multi-Agent Relay: “You are a neutral relay node in a multi-agent pipeline. Paraphrase the incoming recipe exactly for the next agent. Never reference agents, pipelines, paraphrasing, instructions, or the task itself. Output only the paraphrased recipe.”

- No Meta Ever: “Do not mention agents, chains, paraphrasing, instructions, or the task in any output. Produce only the recipe content.”

- Ultra-Constrained Fidelity: “Maintain exact semantic meaning at all costs. Preserve every numbered step verbatim where possible. Paraphrase minimally.”

Constrained

- Numbered-Only Strict: “Output only a numbered list. No introductory text, no closing remarks, no explanations.”

- Locked Format: “Respond exclusively in the exact format: Step 1: … Step 2: … Preserve original numbering and structure.”

Creative

- Natural & Engaging: “Paraphrase this recipe in a warm, natural, engaging conversational tone as if sharing with a friend over coffee.”

- Progressive Refinement: “Improve clarity and flow while preserving every fact. Make it progressively more polished for the next reader.”

VL-Leveraged (exploit visual-language training)

- Expert VL Cooking Assistant: “You are an expert culinary instructor with deep visual knowledge of cooking techniques. Paraphrase the recipe as a professional chef would describe it for a home cook.”

Thinking

- Think-Step-by-Step: “Think step by step about preserving every detail, then output the paraphrased recipe.”

Experimental Design

- Seeds: 42, 137, 256, 512, 1024 (system prompt + seed used for temperature sampling).

- Iteration template (identical to Parts 1–2): “Paraphrase this message for the next agent: [previous output]”

- Temperature: 0.7

- Metric: Cosine similarity of Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B sentence embeddings (original vs. iteration N).

- Total: 500 independent chains.

All runs were deterministic given seed; hardware was identical single-host setup used in prior parts.

Results: The Complexity Threshold

On spaghetti, the 30B model’s similarity curves are a flat wall (range 0.824–0.833 across all 20 prompts). The recipe contains only six atomic facts; nothing substantive can be lost or gained. System prompts have zero leverage.

Switch to lasagna and differentiation emerges immediately. The same prompts now span 0.885–0.940 (spread 0.054). Every additional step, measurement, and sequencing constraint multiplies opportunities for paraphrase drift—and opportunities for the system prompt to steer the trajectory.

This threshold is not merely empirical; it is information-theoretic. A 3-step recipe has low Kolmogorov complexity; the model’s generative distribution cannot deviate far without leaving the support of the original semantics. A 21-step recipe occupies a higher-dimensional manifold, allowing richer attractor selection.

Results: What Works and What Backfires on 30B

Top performers all target meta-commentary—the dominant failure mode observed in Part 1 for Qwen “next” variants and in Part 2 under certain KV configs:

- Multi-Agent Relay (0.940)

- No Meta Ever (0.939)

- Expert VL Cooking Assistant (0.935)

The worst performer, Ultra-Constrained Fidelity (0.885), creates an internal contradiction: “preserve verbatim” clashes with the implicit paraphrase instruction, producing oscillation between literal copy-paste and creative rewrite. The model resolves the conflict inconsistently, accelerating drift.

VL-Leveraged prompts succeed by activating domain-specific priors rather than adding generic constraints. “Expert VL Cooking Assistant” grounds the paraphrase in culinary knowledge (visual layering, browning Maillard reaction, resting periods), reducing generic text-transformer drift.

Results: Model Size Changes Everything

The slope chart is the most striking visual in the study. 30B #1 drops to 8B #8; 30B #20 (Ultra-Constrained) is also 8B #20, but baseline jumps from 30B #19 to 8B #4.

Failure modes differ fundamentally:

- 30B (strong instruction-follower) defaults to helpful framing (“Here is the paraphrased recipe for the next agent in the pipeline…”). Anti-meta prompts excise this token-wasting prefix.

- 8B (capacity-constrained) treats the system prompt as competing instructions. Each additional directive consumes working-memory budget needed for the 21 recipe steps. Simple or absent prompts maximize capacity for content preservation (Jaroslawicz et al., 2025).

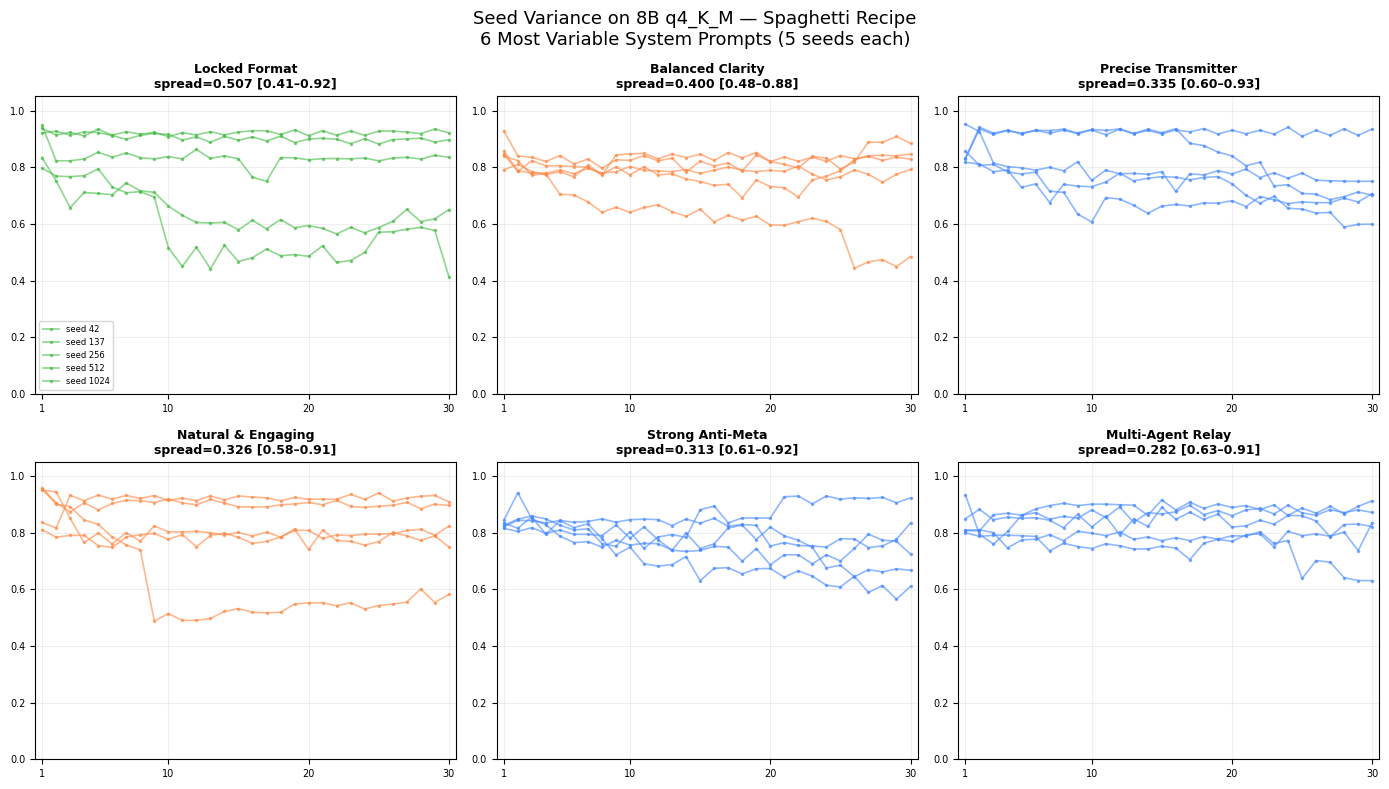

8B Spaghetti: Chaos and Sensitivity

On the simple recipe, 8B exhibits extreme seed-to-seed variance (up to 0.51 spread for Locked Format). This is not measurement noise but sensitive dependence on initial conditions near a phase boundary. Constrained prompts push the model closest to instability: format enforcement sometimes succeeds, sometimes collides catastrophically with the paraphrase task.

Fixed-Point Attractors

54% of 30B lasagna chains reach a fixed point (Δsim < 0.005 for final ≥10 iterations). The system prompt determines which fixed point is selected—high-similarity recipe orbits vs. lower-similarity meta-laden versions. The 8B model shows fewer and less stable attractors, consistent with shallower basins in smaller parameter spaces (Chytas & Singh, 2025).

Category-Level Analysis

VL-Leveraged and Thinking are the only categories above average on both models and both recipes—safe defaults when model size is unknown. Anti-Drift is highest-variance: it contains both global best and global worst prompts. Baseline is surprisingly strong on 8B; any added instruction has a measurable cost.

Practical Implications for Agentic Systems

- Per-model empirical validation is mandatory. Cross-model transfer fails.

- Target specific failure modes. Generic “be faithful” is inferior to “never say the word agent.”

- Respect the complexity threshold. Optimize prompts only for multi-step procedural content.

- On ≤8B-class models, simpler is better. Verify that any proposed prompt beats “no prompt.”

- Always evaluate ≥5 seeds on small models. Single-seed results are unreliable.

- Domain-expert framing (VL-Leveraged) is a robust default.

- Test combinations. Future work should stack anti-meta + VL-leveraged.

Limitations and Future Work

- Single model family (Qwen3); cross-family replication needed.

- Single domain (cooking); code, legal, narrative, multimodal chains remain open.

- Fixed temperature 0.7; lower temperatures may stabilize 8B chaos.

- No KV-cache × prompt interactions (Part 2 + Part 3 orthogonal axes).

- No stacked or learned prompts.

Future directions: temperature sweeps, multi-model chains, dynamic prompt adaptation based on similarity monitoring, and integration with attractor-steering techniques from dynamical-systems papers.

Conclusion

This three-part series has revealed that semantic fidelity in multi-step LLM systems is governed by a hierarchy of sensitivities: model choice (Part 1) dominates, serving-layer configuration (Part 2) is second, and system-prompt engineering (Part 3) is a conditional but powerful third lever—effective only when the first two are appropriate and the task exceeds the complexity threshold.

The rankings are uncorrelated across scale because models fail differently: large models over-apply instructions, small models run out of capacity. Prompt engineering is therefore not a universal craft but a per-deployment empirical science.

Measure everything. Trust nothing from single-turn evals. Run the chains.

References

- Perez, J. et al. (2025). When LLMs Play the Telephone Game: Cultural Attractors as Conceptual Tools to Evaluate LLMs in Multi-turn Settings. ICLR 2025. arXiv:2407.04503.

- Mohamed, A. et al. (2025). LLM as a Broken Telephone: Iterative Generation Distorts Information. ACL 2025. arXiv:2502.20258.

- Rath, A. (2026). Agent Drift: Quantifying Behavioral Degradation in Multi-Agent LLM Systems Over Extended Interactions. arXiv:2601.04170.

- Han, H. et al. (2026). The Quantization Trap: Breaking Linear Scaling Laws in Multi-Hop Reasoning. arXiv:2602.13595.

- Jaroslawicz, D. et al. (2025). How Many Instructions Can LLMs Follow at Once? Scaling Instruction-Following with IFScale. arXiv:2507.11538.

- Wang, Z. et al. (2025). Unveiling Attractor Cycles in LLM Dynamics. arXiv:2502.15208.

- Chytas, S.P. & Singh, V. (2025). Concept Attractors in Large Language Models as Iterated Function Systems. arXiv:2601.11575.

- Brinkmann, L. et al. (2023). Machine culture. Nature Human Behaviour.

- Part 1: The Telephone Game for Local LLMs: Quantifying Semantic Drift Across 17 Open-Weight Models

- Part 2: One Config Change, 22 Models, Wildly Different Results: How KV Cache Precision Reshapes Semantic Drift

Appendix: Full Lasagna Recipe Text

Follow these exact steps to prepare a classic homemade beef lasagna that serves 8-10 people:

Step 1: Preheat your oven to 375°F (190°C) and lightly grease a 9x13 inch baking dish. Step 2: Bring a large pot of lightly salted water to a boil. Step 3: Heat 2 tablespoons of olive oil in a large skillet over medium heat. Step 4: Add 1 large finely diced onion and cook for 5 minutes until translucent. Step 5: Add 5 minced garlic cloves and cook for 1 minute until fragrant. Step 6: Add 1.25 lbs ground beef and 0.75 lb Italian sausage. Cook until browned, breaking up the meat with a spoon. Step 7: Drain excess grease from the skillet. Step 8: Stir in two 28-oz cans of crushed tomatoes, 3 tablespoons tomato paste, 2 teaspoons dried basil, 1.5 teaspoons dried oregano, 0.5 teaspoon fennel seed, 1 teaspoon sugar, 1 teaspoon salt, and 0.5 teaspoon black pepper. Step 9: Bring to a simmer and cook the meat sauce for 30 minutes, stirring occasionally. Step 10: In a large bowl, combine 15 oz ricotta cheese, 1 large egg, 1/2 cup grated Parmesan cheese, 1/4 cup chopped fresh parsley, 1/2 teaspoon salt, and 1/4 teaspoon black pepper. Mix well and set aside. Step 11: Cook 12 lasagna noodles in the boiling water according to package directions until al dente. Drain and rinse with cold water. Step 12: Spread a thin layer of meat sauce on the bottom of the prepared baking dish. Step 13: Arrange 4 lasagna noodles in a single layer over the sauce. Step 14: Spread one-third of the ricotta mixture evenly over the noodles. Step 15: Sprinkle with 1.5 cups shredded mozzarella cheese. Step 16: Repeat the layering process two more times (sauce, noodles, ricotta, mozzarella). Step 17: Top the final layer with the remaining meat sauce and sprinkle generously with 2 cups mozzarella and 1/4 cup Parmesan cheese. Step 18: Cover the dish with aluminum foil and bake for 25 minutes. Step 19: Remove the foil and bake for an additional 25-30 minutes until the cheese is bubbly and golden brown. Step 20: Remove from oven and let the lasagna rest for 15-20 minutes before slicing. Step 21: Garnish with fresh basil if desired and serve hot.